The use of AI images is not just an issue for editorial purposes. Marketing, advertising and other forms of communication may also want or need to illustrate work with images to attract readers or to present particular points. Martin Bryant is the founder of tech communications agency Big Revolution and has spent time in his career as an editor and tech writer.

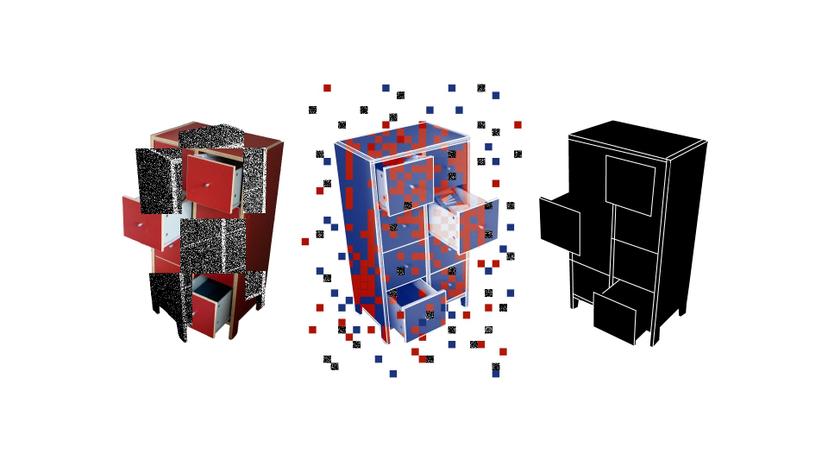

“AI falls into that same category as things like cyber security where there are no really good images because a lot of it happens in code,” he says. “We see it in outcomes but we don’t see the actual process so illustration falls back on lazy stereotypes. It’s a similar case with cyber security, you’ll see the criminal with the swag bag and face mask stooped over a keyboard and with AI there’s the red-eyed Terminator robot or it’s really cheesy robots that look like sixties sci-fi.”

The influence of sci-fi images in AI is strong and one that can make reporters and editors uncomfortable with their visal options. “ “Whenever I have tried to illustrate AI I’ve always felt like I am short changing people because it ends up being stock images or unnecessarily dystopian and that does a disservice to AI. It doesn’t represent AI as it is now. If you’re talking about the future of AI, it might be dystopian, but it might not be and that’s entirely in our hands as a species how we want AI to influence our lives,” Martin says. “If you are writing about killer robots then maybe a Terminator might be OK to use but if you’re talking about the latest innovation from DeepMind then it’s just going to distort the public understand of AI either to inflate their expectations of what is possible today or it makes them fearful for the future.”

I should be open here about how I know Martin. We worked together for the online tech publication The Next Web where he was my managing editor and I was UK editor some years ago. We are both very familiar with the pressures of getting fast-moving tech news out online, to be competitive with other outlets and of course to break news stories. The speed at which we work in news has an impact on the choices we can make.

“If it’s news you need to get out quickly, then you just need to get it out fast and you are bound to go for something you have used in the past so it’s ready in the CMS (Content management system – the ‘back end’ of a website where text and images are added.),” Martin says. “You might find some robots or in a stock image library there will be cliches and you just have to go with something that makes some sense to readers. It’s not ideal but you hope that people will read the story and not be too influenced by the image – but a piece always needs an image.”

That’s an interesting point that Martin is making. In order to reach a readership, lots of publications rely on social media to distribute news. It was crowded when we worked together and it sometimes feels even more packed today. Think about the news outlets you follow on Twitter or Facebook, then add to this your friends, contacts and interesting people you like to follow and the amount of output they create with links to news they are reading and want to comment upon. It means we are bombarded with all sorts of images whenever we start scrolling and to stand out in this crowd, you’re going to need something really eye-catching to make someone slow down and read.

“If it’s a more considered feature piece then there’s maybe more scope for a variety of images, like pictures of the people involved, CEOs, researchers and business leaders,” Martin says. “You might be able to get images commissioned or you can think about the content of the piece to get product pictures, this works for topics like driverless cars. But there is still time pressure and even with a feature, unless you are a well-resourced newsroom with a decent budget, you are likely to be cutting corners on images.”

Marketing exciting AI

It’s not just the news that is hungry for images of AI. Marketing, advertising and other communications are also battling for our attention and finding the right image to pull in readers, clicks or getting people to use a product is important. Important, but is it always accurate? Martin works with and has covered news of countless startup companies, some of which use AI as a core component of their business proposition.

“They need to think about potential outcomes when they are communicating,” he says “Say there is a breakthrough in deep neural AI or something it’s going to be interesting to academics and engineers, the average person is not going to get that because a lot of it requires an understanding of how this technology works and so you often need to push startups to think about what it could do, what they are happy with saying is a positive outcome.”

This matches the thinking of many discussions I have had about art and the representation of AI. In order to engage with people, it can be easier to show them different topics of use and influence from agriculture to medical care or dating. These topics are far more familiar to a wider audience than a schematic for an adversarial network. But claiming an outcome can also be a thorny issue for some company leaders.

“A lot of startup founders from an academic background in AI tend to be cautious about being too prescriptive about how their technology could be used because often if they have not fully productised their work in an offering to a specific market,” Martin explains. “They need to really think about optimistic outcomes about how their tech can make the world better but not oversell it. We’re not saying it’s going to bring about world peace, but if they really think of examples of how the AI can help people in their everyday lives this will help people engage with making the leap from a tech breakthrough they don’t understand to really getting why it’s useful.”

Overstating AI

AI now appears to be everywhere. It’s a term that has broken out from academia, through engineering and into business, advertising and mainstream media. This is great, it can mean more funding, more research, progress and ethical monitoring and attention. But when tech gets buzzy, there’s a risk that it will be overstated and misconstrued.

“There’s definitely a sense of wanting to play up AI,” Martin says. “There’s a sense that companies have to say ‘look at our AI!’ when actually that might be overselling what is basic technology behind the scenes. Even if it’s more developed than that, they have to be careful. I think focusing on outcomes rather than technologies is always the best approach. So instead of saying ‘our amazing, groundbreaking AI technology does this’ – focusing on what outcomes you can deliver that no one else can because of that technology is far more important.

As we have both worked in tech for so long, the buzzword buzzkill is a familiar situation and one that can end up with less excitement and more of an eyeroll. Martin shared some past examples we could learn from, “It’s so hilarious now,” he says. “A few years ago everything had to have a location element, it was the hot new thing and now the idea of an app knowing your location and doing something relevant to it is nothing. But for a while it was the hottest thing.

“Gamification was a buzzword too. Now gamification is a feature in lots and lots of apps, Duolingo is a great example but it’s subtly used in other areas but for a while startups would pitch themselves saying ‘we are the gamified version of X’.”

But the overuse of language and their accompanying images is far from over and it’s not just AI that suffers. “Blockchain keeps rearing its head,” Martin points out. “It’s Web3 now, slightly further along the line but the problem with Web3 and AI is that there’s a lot of serious and thoughtful work happening but people go ahead with ‘the blockchain version of X or web3 version of Y’ and because it’s not ready yet or it’s far too complicated for the mainstream, it ends up disillusioning people. I think you see this a bit with AI too but Web3 is the prime example at the moment and it’s been there in various forms for a long time now.”

To avoid bad visuals and buzzword bingo in the reporting of AI, it’s clear through Martin’s experience that outcomes are a key way of connecting with readers. AI can be a tricky one to wrap your head around if you’re not working in tech, but it’s not that hard when it’s clearly explained.”It really helps people understand what AI is doing for them today rather than thinking of it as something mysterious or a black box of tricks,” Martin says. “That box of tricks can make you sound more competitive but you can’t lie to people about it and you need to focus on outcomes that help people understand clearly what you can do. You’ll not only help people’s understanding of your product but also the general public’s knowledge of what AI can really do for them.”