Artist contributions to the Better Images of AI library have always served a really important role in relation to fostering understanding and critical thinking about AI technologies and their context. Images facilitate deeper inquiries into the nature of AI, its history, and ethical, social, political and legal implications.

When artists create better images of AI, they often have to grapple with these narratives in their attempts to more realistically portray the technology and point towards its strengths and weaknesses. Furthermore, as artists freely share these images in our library, others can benefit from learning about the artist’s own internal motivations (which are provided in the descriptions) but the images can also inspire users’ own musings.

In this series of blog posts, some of our volunteer stewards are each taking turns to choose an image from the Archival Images of AI collection and unpack the artist’s processes and explore what that image means to them.

At the end of 2024, we released the Archival Images of AI Playbook with AIxDESIGN and the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision. The playbook explores how existing images – especially those from digital heritage collections – can help us craft more meaningful visual narratives about AI. Through various image-makers’ own attempts to make better images of AI, the playbook shares numerous techniques which can teach you how to transform existing images into new creations.

Here, Zoya Yasmine unpacks ‘Ways of Seeing’ – Nadia Piet’s (an image-maker) own better image of AI that was created for the playbook. Zoya comments on how it is a really valuable image to depict the way that text-to-image generators ‘learn’ how to generate their output creations. Zoya considers how this image relates to copyright law (she’s a bit of an intellectual property nerd) and the discussions about whether AI companies should be able to use individual’s work to train their systems without explicit consent or remuneration.

Nadia Piet + AIxDESIGN & Archival Images of AI / Better Images of AI / Ways of Seeing / CC-BY 4.0

‘Ways of Seeing’ by Nadia Piet

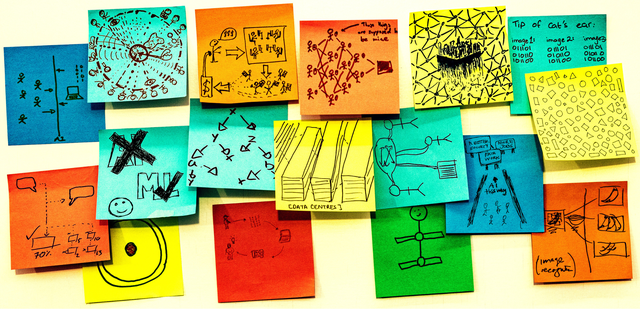

This diptych contrasts human and computational ways of seeing: one riddled with memory and meaning, the other devoid of emotional association and capable of structural analysis. The left pane shows an illustration from Tom Seidmann-Freud’s Book of Hare Stories (1924) which portrays a whimsical, surreal scene that is both playful and uncanny. On the right, the illustration is reduced to a computational rendering, with each of its superpixels (16×16) fragmented and sorted by visual complexity with a compression algorithm.

Copyright and training AI systems

Training AI systems requires substantial amounts of input data – from images, videos, texts and other content. Based on the data from these materials, AI systems can ‘learn’ how to make predictions and provide outputs. However, lots of these materials used to train AI systems are often protected by copyright owned by another parties which raises complex questions about ownership and the legality of using such data without permission.

In the UK, Getty Images filed a lawsuit against Stability AI (developers of a text-to-image model called Stable Diffusion) claiming that 7.3 million of its images were unlawfully scrapped from its website to train Stability AI’s model. Similarly, Mumsnet has launched a legal complaint against OpenAI, the developer of ChatGPT, accusing the AI company of scraping content from its site (with over 6 billion words shared by community members) without consent.

The UK’s Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1998 (the Act) provides companies like Getty Images and Mumsnet with copyright protection over their databases and assets. So unless an exception applies, permission (through a license) is required if other parties wish to reproduce or copy the content. Section 29(A) of the Act provides an exception which permits copies of any copyright protected material for the purposes of Text and Data Mining (TDM) without a specific license. But, this lenient provision is for non-commercial purposes only. Although the status of AI systems like Stable Diffusion and ChatGPT have not been tested before the courts yet, they are likely to fall outside the scope of non-commercial purposes.

TDM is the automated technique used to extract and analyse vast amounts of online materials to reveal relationships and patterns in the data. TDM has become an increasingly valuable tool to train lucrative generative AI systems on mass amounts of materials scraped from the Internet. It becomes clear that AI models cannot be developed or built efficiently without input data that has been created by human artists, researchers, writers, photographers, publishers, and creators. However, as much of their works are being used without payment or attribution by AI companies, big tech companies are essentially ‘freeriding’ on the works of the creative industry who have invested significant time, effort, and resources into producing such rich works.

How does this image relate to current debates about copyright and AI training?

When I saw this image, it really prompted me to think about the training process of AI systems and the purpose of the copyright system. ‘Ways of Seeing’ has stimulated my own thoughts about how computational models ‘learn’ and ‘see’ in contrast to human creators.

Text-to-image AI generators (like Stable Diffusion or Midjourney) are repeatedly trained on thousands of images which allow the models to ‘learn’ to identify patterns, like what common objects and colours look like, and then reproduce these patterns when instructed to create new images. While Piet’s image has been designed to illustrate a ‘compression algorithm’ process, I think it also serves as a useful visual to reflect how AI processes visual data computationally, reducing it to pixels, patterns, or latent features.

It’s important to note that often the images generated by AI models will not necessarily be exact copies of the original images used in the training process – but instead, they serve as statistical approximations of training data which have informed the model’s overall understanding of how objects are represented.

It’s interesting to think about this in relation to copyright and what this legal framework serves to protect. Copyright stands to protect the creative expression of works – for example, the lighting, exposure, filter, or positioning of an image – but not the ideas themselves. The reason that copyright law focuses on these elements is because they reflect the creator’s own unique thoughts and originality. However, as Piet’s illustration can usefully demonstrate, what is significant about the AI training process for copyright law is that often TDM is often not used to extract the protected expression of the materials.

To train AI models, it is often the factual elements of the work that might be the most valuable (as opposed to the creative aspects). The training process relies on the broad visual features of the images, rather than specific artistic choices. For example, when training text-to-image models, TDM is not often used to extract data about the lighting techniques which are employed to make an image of a cat particularly appealing. Instead, the accessibility to images of cats which detail the features that resemble a cat (fur, whiskers, big eyes, paws) are what’s important. In Piet’s image, the protectable parts of the illustration from the ‘Book of Hare Stories’ would subsist in the artistic style and execution – for example, the way that the hare and other elements are drawn, the placement and interaction of the elements, and the overall design of the image.

The specific challenge for copyright law is that AI companies are unable to capture these ‘unprotectable’ factual elements of materials without making a copy or storing the protected parts (Lemley and Casey, 2020). I think Nadia’s image really highlights the transformation of artwork into fragmented ‘data’ for training systems which challenges our understanding of creativity and originality.

My thoughts above are not to suggest that AI companies should be able to freely use copyright protected works as training data for their models without remunerating or seeking permission from copyright owners. Instead, the way that TDM and generative AI ‘re-imagine’ the value of these ‘unprotectable’ elements means that AI companies still freeride on creator’s materials. Therefore, AI companies should be required to explicitly license copyright-protected materials used to train their systems so creators are provided with proper control over their works (you can read more about my thoughts here).

Also, I do not deny that there are generative AI systems that aim to reproduce a particular artist’s style – see here. In these instances, I think it would be easier to prove that there was copyright infringement since these are a clear reproduction of ‘protected elements’. However, if this is not the purpose of the AI tool, developers try to avoid the outputs replicating training data too similarly as this can open them up more easily to copyright infringement for both the input (as discussed in this piece) but also the output image (see here for a discussion).

My favourite part of Nadia Piet’s image

I think my favourite part of the image is the choice of illustration used to represent computational processing. As Nadia writes in her description, Tom Seidmann-Freud’s illustration depicts a “whimsical, surreal scene that is both playful and uncanny”. Tom, an Austrian-Jewish painter and children’s book author and illustrator (and also Sigmund Freud’s niece), led a short life and she died of an overdose of sleeping pills in 1930 at age 37 after the death of her husband a few months prior.

“The Hare and the Well” (Left), “Fable of the Hares and the Frogs” (Middle), “Why the Hare Has No Tail” (Right) by Tom Seidmann-Freud derived in the Public Domain Review

After Tom’s death, the Nazis came to power and attempted to destroy much of the art she had created as part of the purge of Jewish authors. Luckily, Tom’s family and art lovers were able to preserve much of her work. I think Nadia’s choice of this image critiques what might be ‘lost’ when rich, meaningful art is reduced to AI’s structural analysis.

A second point, although not related exactly to the image, is the very thoughtful title, ‘Ways of Seeing’. ‘Ways of Seeing’ was a 1972 BBC television series and book created by John Berger. In the series, Berger criticised traditional Western cultural aesthetics by raising questions about hidden ideologies in visual images like the male gaze embedded in the female nude. He also examined what had changed in our ‘ways of seeing’ in the time between the art was made and the present day. Side note: I think Berger’s would have been a huge fan of Better Images of AI.

In a similar vein, Nadia has used Seidmann-Freud’s art as a way to explore new parallels with technology like AI which would not have been thought about at the time the work was created. In addition, Nadia’s work serves as an invitation to see and understand AI differently, and like Berges, her work supports artists around the world.

The value of Nadia’s ‘better image of AI’ for copyright discussions

As Nadia writes in the description, Tom Seidmann-Freud’s illustration was derived from the Public Domain Review, where it is written that “Hares have been known to serve as messengers between the conscious world and the deeper warrens of the mind”. From my perspective, Nadia’s whole image acts as a messenger to convey information about the two differing modes of seeing between humans and AI models.

We need better images of AI like this. Especially for the purposes of copyright law so we can have more meaningful and informed conversations about the nature of AI and its training processes. All too often, in conversations about AI and creativity, images used depict humanoid robots painting on a canvas or hands snatching works.

‘AI art theft’ illustration by Nicholas Konrad (Left) and Copyright and AI image (Right)

These images create misleading visual metaphors that suggest that AI is directly engaging in creative acts in the same way that humans do. Additionally, visuals showing AI ‘stealing’ works reduce the complex legal and ethical debates around copyright, licensing, and data training to overly simplified, fear-evoking concepts.

Thus, better images of AI, like ‘Ways of Seeing’, can serve a vital role as a messenger to represent the reality of how AI systems are developed. This paves the way for more constructive legal dialogues around intellectual property and AI that protect creator’s rights, while allowing for the development of AI technologies based on consented, legally acquired datasets.

About the author

Zoya Yasmine (she/her) is a current PhD student exploring the intersection between intellectual property, data, and medical AI. She grew up in Wales and in her spare time she enjoys playing tennis, puzzling, and watching TV (mostly Dragon’s Den and Made in Chelsea). Zoya is also a volunteer steward for Better Images of AI and part of many student societies including AI in Medicine, AI Ethics, Ethics in Mathematics & MedTech.

This post was also kindly edited by Tristan Ferne – lead producer/researcher at BBC Research & Development.

If you want to contribute to our new blog series, ‘Through My Eyes’, by selecting an image from the Archival Images of AI collection and exploring what the image means to you, get in touch (info@betterimagesofai.org)