In this blog post, Harriet Humfress (a volunteer steward) explores Yutong Liu’s (artist) collection of “Digital Nomad” images which were submitted as part of the “Digital Dialogues” competition that we ran in collaboration with Digit this summer. Yutong’s images were awarded as winners in two of the categories.

Harriet gives a creative reading of Yutong’s work drawing upon her experience as a fine art student at the University of Oxford. She highlights how the “Digital Nomad” series and Yutong’s illustrative approaches centre the context of artistic creation and how the body always precedes the digital. Harriet argues that these are two features that cannot be recreated in AI-generated artwork, making Yutong’s work so fitting to visualise how digital transformation is -and isn’t- changing our existing practices.

I have a really clunky keyboard.

It’s bright green, and my gel extensions snag between the gaps, but its clack is so satisfying.

It almost looks like the keyboard in “Beyond the Cubical” (although my desk is much messier). I, too, have Post-it notes skirting my monitor, papers I’ve forgotten to read peek out sheepishly from under my trackpad, and my cables never behave, so I shove them behind the desk every time I sit down.

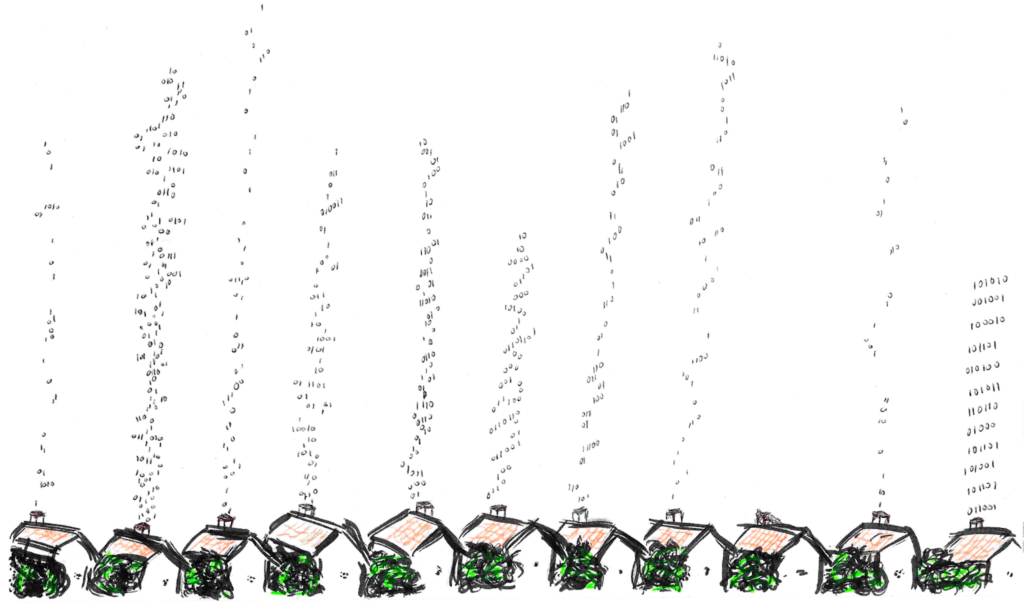

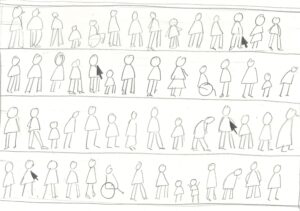

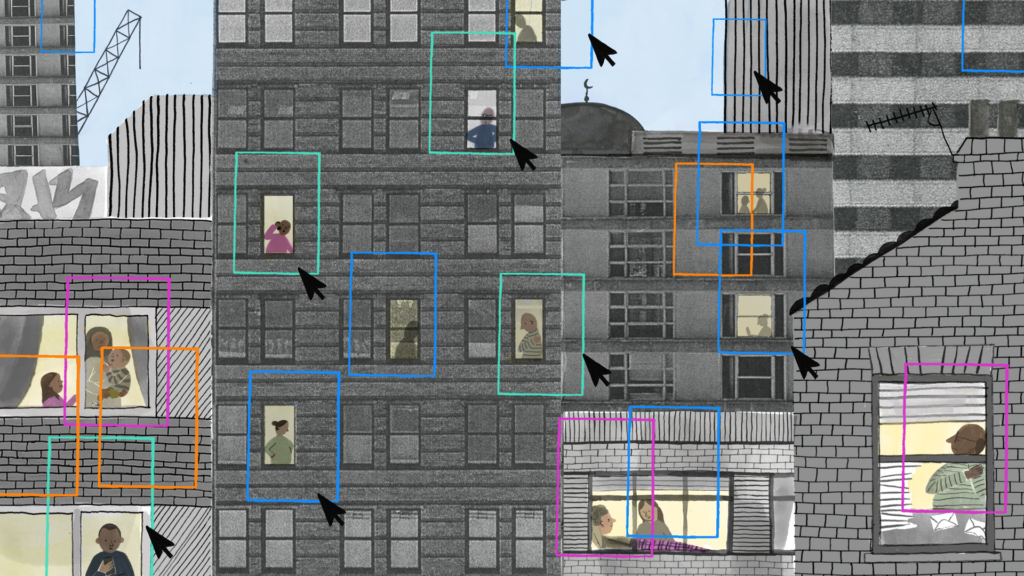

Before any part of us is online, we are situated. ‘Across time’ makes that felt; the trench-coated worker feels the heat from his laptop building on his thigh, the man at the printer feels the low hum through his forearm and smells the warm, inky breath of the paper, and, across the desk, a woman’s shoulders tighten and her calves pulse after hunching over a laptop for too long.

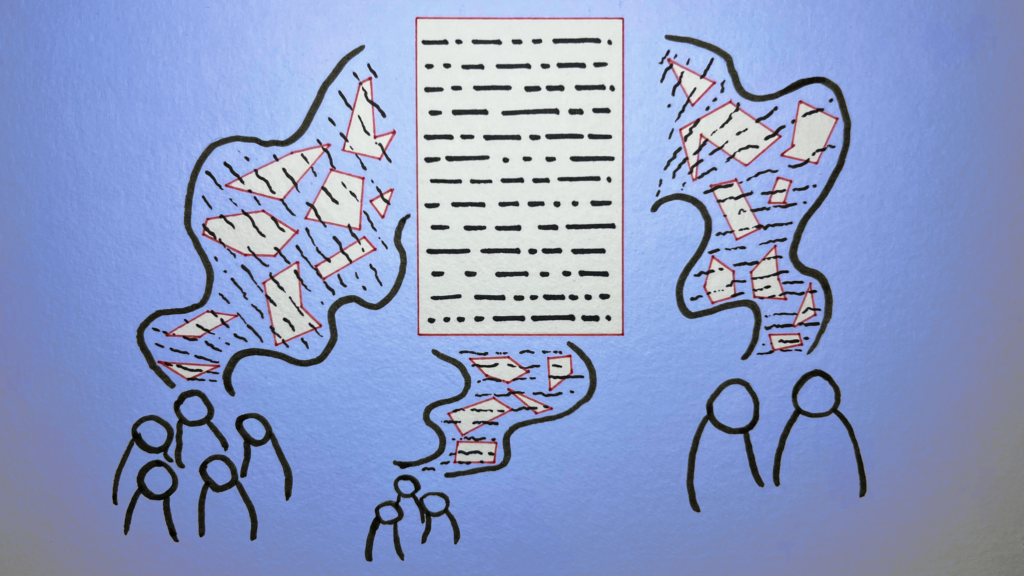

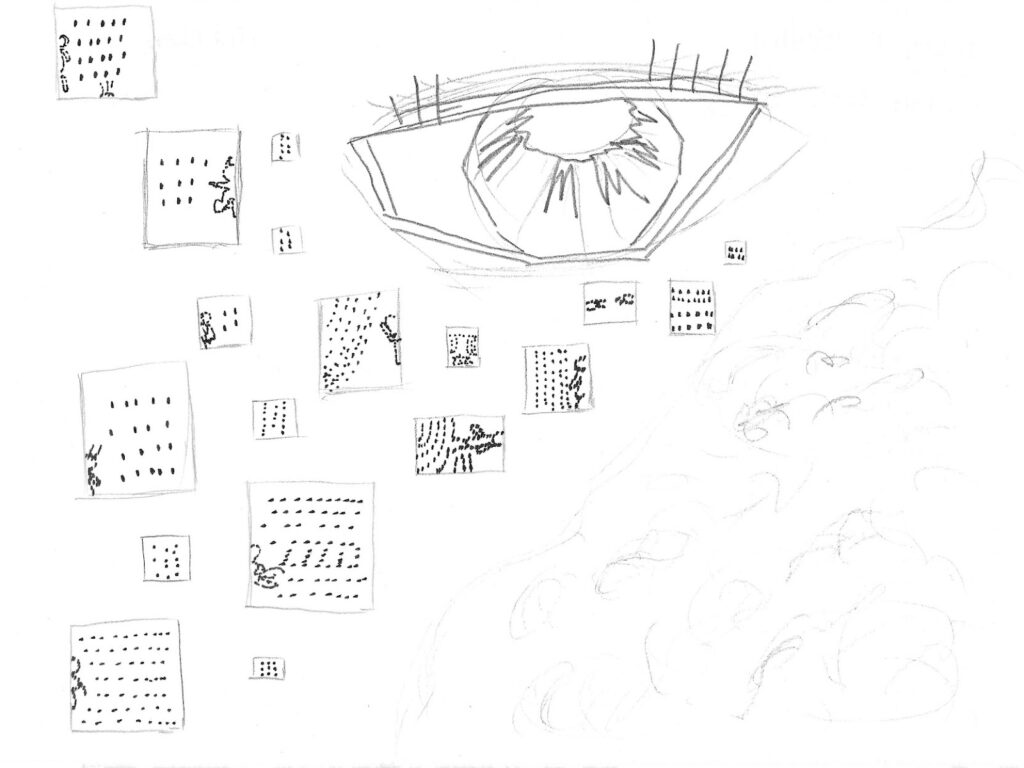

Once we are situated, our habits spill outwards into the digital realm. Our scrolls, pauses, hesitation and clicks become data that reveal us to the system more than the system reveals itself to us. Alexander Galloway argues in ‘The Interface Effect’, that “the world materialises in our image”, and “Digital Based Connection” visualises this. Yutong’s character’s all navigate the same landscape of rolling hills and threaded cables, but they exist there differently; one runs breathlessly, with his laptop outstretched, while another lies back beneath a laptop turned parasol, nonchalantly bathing in its glow. The digital realm is less like a sealed second world, but like a map we make as we move.

But, how do we get there?

The body precedes the digital

“So, we may arrive on screen as a cursor, but the work that gets us there is all shoulder, wrist, and fingertips.” – Harriet Humfress

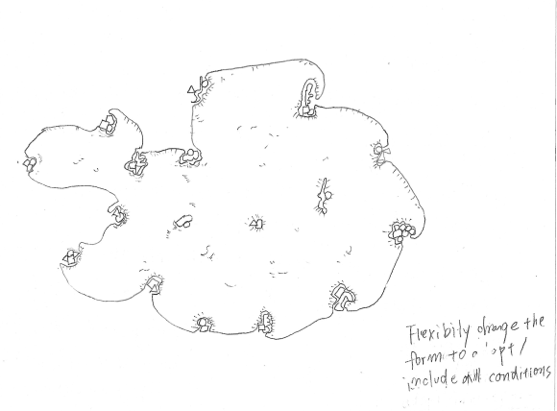

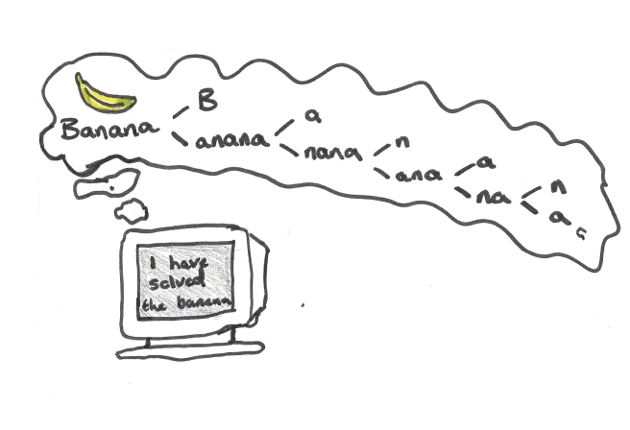

Yutong’s images insist that the body precedes the digital. Once online, our postures and clicks are compressed into a single point of agency: the cursor. Yutong literalises this proxy with her cursor-birds; these tiny, winged cursors keep the image in motion, reminding us that digital work advances click by click.”

“The idea of the mouse–cursor birds came from thinking about how almost every action we take on a computer involves the presence of the cursor. Without it, we can hardly do anything. So, I added them to represent the constant participation of the cursor in digital nomad work. Every “click” sets off or completes another task.” – Yutong Liu

Throughout her work, Yutong doesn’t anthropomorphise AI, she treats it almost as weather, as ambient infrastructure, or perhaps a climate.

“To me, AI is in every screen. As long as there’s a screen and a connection to the internet, AI is already there—quietly influencing and facilitating everything in the background.” – Yutong Liu In ‘Digital Based Connection’, wires drape across the hills like isobars and laptops swell into oversized furniture and characters live together with the network, loosely tethered to an apple tree-router. For Yutong, these connections are her “way of illustrating how digital nomads transmit ideas within a shared space—both physical and virtual.” She imagines that “once these ideas accumulate, the tower transforms into an apple tree, with each apple representing a spark of human thought—shining, ripe, and ready to be shared.” The network is a climate we inhabit, not a figure we meet, which is why, for Yutong, AI doesn’t need a face at all, as it is present wherever a screen is lit.

The click-clack of my keyboard will never reach this file, but it will shape how it is written as my finger gets caught, and I spam the backspace, losing my train of thought. This is what Yutong describes as “traces of experiences”; digital files don’t stain, but Yutong’s drawing situations lodge themselves into her work. These traces are why her pictures feel lived in.

AI and the ‘context debt‘

“Try to imagine unzipping your skin and stepping outside. What would step out? How would we exist without our senses?” – Harriet Humfress

iPads and digital tools are Yutong’s main mediums, and offer near infinite ‘undo’ and precision, where the artist has complete control over the machine, and are sometimes marketed as ‘frictionless’ and ‘seamless’. This precision used to play an important role in Yutong’s process, but over time, she realised that “something was missing. Those ultra-clean, overly perfect lines started to feel rigid and lifeless” and she’s consciously shifted her approach: “I’ve come to embrace a certain level of unpredictability and imperfection in my work – because that’s what gives it authenticity and emotion”.

Rather than being nostalgic for paper, Yutong’s inclusion of these “traces” allows place, time, and the body to survive a frictionless tool.

“You can find traces of experiences in the visual element of my ‘Digital Nomads’ series. My inspiration comes from life itself, and I naturally project the life I’m living into the images I create. So even though digital images don’t physically create stains like paper does, I believe a sense of place can still seep in.” – Yutong Liu

These “traces” are a breadcrumb trail. Follow it and you arrive at context.

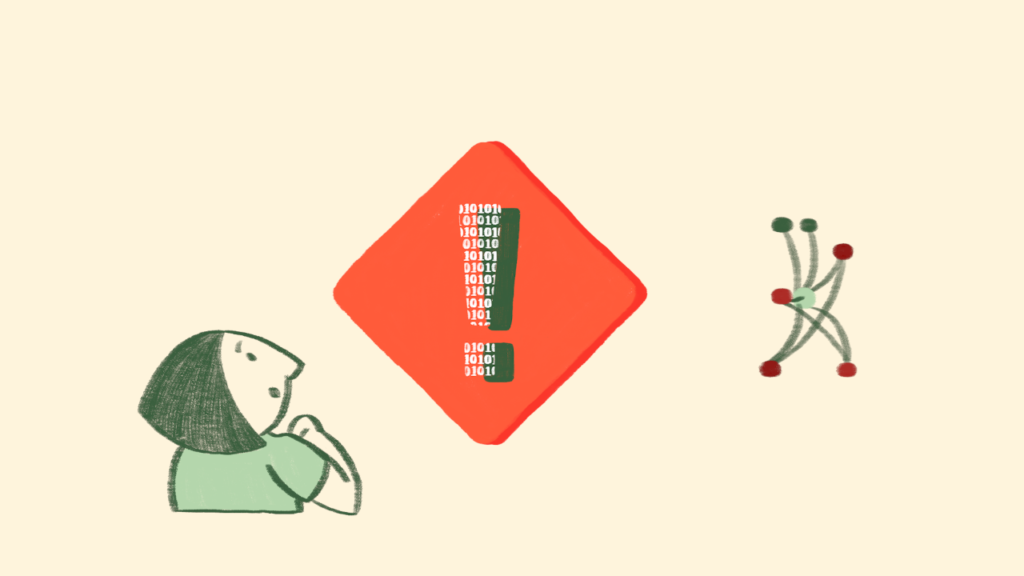

In her Zine, ‘The Balance Between AI and Human’, Yutong muses on the role of the creative co-existing with AI. She recalls reading Adam Nemeth’s 2023 article and describes getting “chills”. What struck her was the idea that context lives in the gap between theory and practice, a space “for new narratives”.

“My art contained my context, a part that AI cannot replicate.” – Yutong Liu

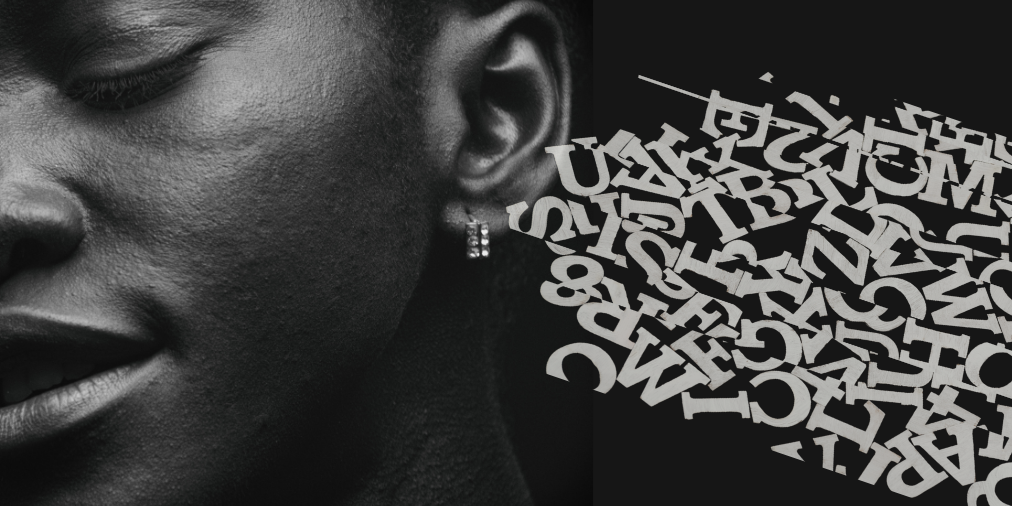

AI may be able to describe or recognise the green of a lime, its bumpy skin, and sour taste, but it will never have the embodied knowledge of feeling the ache in your jaw or how saliva floods your mouth, or how the sourness contorts your face. This is the context gap that Yutong’s work operates in. A drawing made on a moving train carries a small tremor in its lines, or a green chosen under yellow café bulbs slips into olive, or how cursor-birds are read with the felt knowledge of strained eyes and a cadence of clicks. In her work, felt experience influences mark-making decisions.

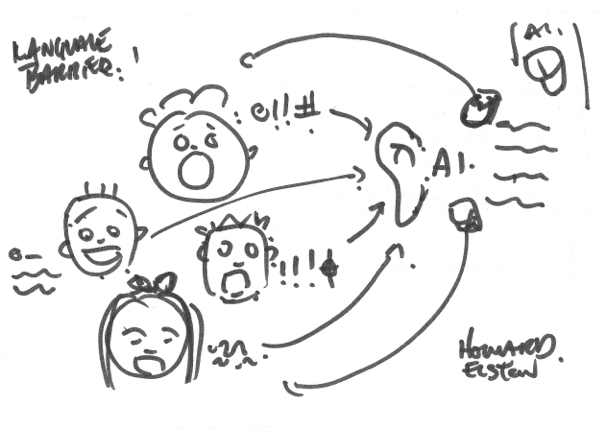

Context also exists outside the body. Yutong describes how “context is also deeply rooted in cultural background […] humans can pick up the real meaning behind someone’s words through micro-expressions or subtle gestures”. Context is a kind of residue that no dataset can convincingly simulate, “something AI cannot currently understand”.

When this residue is thinned out and replaced with set definitions and statistical averages, images read as uncanny or empty. Yutong’s work explores the pushback to AI, and how this is more than just a “new moral panic”. It’s a reaction to context debt.

“The powerful rise of AI has instilled fear in many people, especially designers. […] Many fast-production, culture-less, story-less, and unoriginal companies have started laying off employees, preferring to pay AI companies to save on labour costs”. – Yutong Liu

We have seen moral panics before, and every generation thinks the next is growing up lazier, more dependent on shortcuts, and dangerously unconcerned with craftsmanship. But this cycle feels different this time, something deeper than generational bitterness. Photography and Procreate disrupted traditional expectations for what counts as “real” art, and AI takes this to the extreme by obscuring and displacing authorship and creating without emotional memory or intention.

“It’s precisely this emotional and sensory presence that prevents human-made art from feeling empty. AI- generated work is the product of code and data – produced at speed and lacking in lived experience or authentic emotion.” – Yutong Liu

Look again at the apples ripening on the router-tree, and the tiny corsor’s commute across the sky. Her metaphors feel lived in and handled and funnelled onto the glass of her iPad through the gripping of a stylus; “even with machine learning, AI can only remix what already exists, whereas human imagination is limitless”.

“Sometimes, the images generated by AI look good at first glance, but when you examine the details, they fall apart. They feel lifeless, soulless. It’s not just the vacant expressions in the characters – it’s the outlines, the brushstrokes, the composition. AI tries so hard to be ‘perfect’ that it ends up over-polished, almost sterile”. – Yutong Liu

Despite this sterility, Yutong doesn’t swear off AI or sermonise about its sins. Within her process, she treats AI as a tool and tries to “maintain a balance”, as she doesn’t want her work to “carry a strong AI shadow” but wants her ” audience to see what technology can help us achieve”. The sterility of AI often promises a neat and tidy input-output perfection, but this tidiness can’t stretch further than theory or reach out to context.

Loading up a chatbot, the input bar glows and the cursor blinks, and just out of rhythm to the clunky keys, but mimics the metronome of the typewriter-style loading of a friendly and reassuring response. It’s hard not to feel spoken to. Yutong describes how she “often imagined there was someone behind the screen who could understand me”, but in this supposed collaboration, prompts get nudged, rephrased, synonyms are traded, weights and models are adjusted, undone, redone, and the system obliges in its endless blank obedience. For Yutong, this “feels like an argument, but a very one-sided one. I was the only one talking, while the AI simply followed my instructions obediently – like a submissive assistant with no opinions or boundaries. No matter how much I ‘argued’ or tried to refine the prompt, there was always a disconnect between what I envisioned and what the AI produced.” After a dozen rounds, the almost-right images seem to pile up all glossy and neatly packaged like supermarket meat, but opening them up reveals this ‘conversation’ to be a monologue.

The system appears to understand, but what comes back seems too neat and strangely weightless, and it’s hard to name why. Try to imagine unzipping your skin and stepping outside. What would step out? How would we exist without our senses? Yutong dragged AI frameworks through the screen and into the room, in workshops to act out AI’s rules; ” I used to believe that AI only existed within computers, networks, and screens” but in these workshops “We explored AI through embodied exercises, like prompt-based drawing games or even “Pictionary”-style activities, where one person gives a prompt and another interprets it visually. These exercises helped us dig into the underlying logic of how AI works—and more importantly, how it differs from human output”. The workshops allowed participants to step into the input-output logic with their whole bodies, simulating image generation by hand.

“By investigating AI from a human, physical standpoint, I began to understand more clearly why its outputs often diverge from our expectations, even when we think our prompts are clear. Stepping away from the screen and into embodied, collaborative spaces made the learning process more playful, surprising, and insightful. That’s why I now find real value in exploring AI through workshops—it deepens my understanding in ways a purely screen–based interaction can’t.” – Yutong Liu

Embodying AI as Human-Led Choreography?

“One, two, one, two, the prompt is the cue. The AI answers with plié, jeté, toes pointed and shoulders back, cleanly executing what has been drilled into it. Yutong leads, and the AI responds with the steps it knows. But what if we fed it something new to dance to?” – Harriet Humfress

For Yutong, the act of embodying AI changed how she thought of AI within her process, as it allowed her to “access ideas and insights [she] wouldn’t have reached through screens alone. It gave me new ways to feel and think about what AI is and what it can do. AI has sparked a lot of inspiration and critical thought for me, just as other digital media have also shaped how I generate ideas and interpret the world.” From here, creating with AI seems less like a collaboration and more like a human-led choreography.

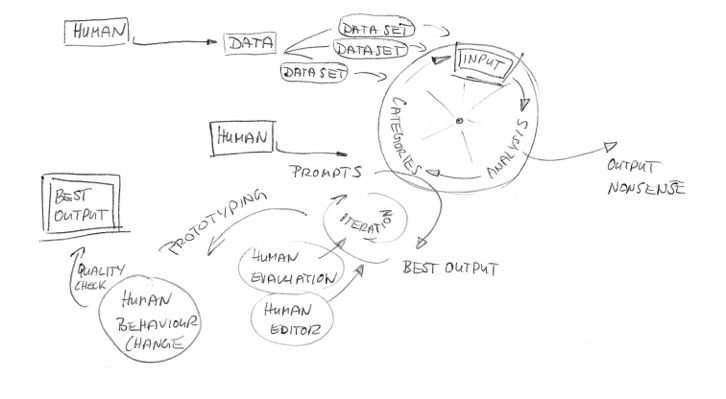

Yutong gives a name to the choreographer: the AI Feeder.

In the last pages of her Zine, Yutong sketches a pragmatic job description for her imagined role of the AI Feeder: contracted artists feed models with tightly curated images, then intervene and correct where the machine falls short, and then use Nightshade (pixel level poisoning that preserves the appearance of images but blocks re-training) on the outputs so they can’t be scraped back into the system. An AI Feeder weaves situated thought and context into the data, embedding what an AI cannot produce on its own, but can be made to follow.

“Illustrators with strong personal styles enter into contract-based collaborations[… ]The company compensates them[… ]The artists then modify parts of the images that do not accurately convey the intended information[… ]Subsequently, the company employs Nightshade[…] to protect both the company’s interests and the copyright interests of the illustrators.” – Yutong Liu

The AI Feeder’s process is less like prompt alchemy and more like rehearsal direction, marking the downbeat, setting constraints, rephrasing, and cutting. Many artist spaces demonise AI, but Yutong provides us with a radical future-facing redirect by prioritising human judgement and artistic integrity in a space where AI can often feel inevitable. She reminds us that ” AI can only generate based on what already exists. But the human mind can drift into unreal, even irrational spaces, and return with ideas no one else could have imagined. We can invent things that don’t yet exist. And I find that endlessly powerful”.

“We as humans have the power of choice, and that’s why I’m not so afraid of AI. Because I have a choice – I can choose to use AI or not in my creative process. As an illustrator, I can choose from various materials – pencils, watercolours, crayons – to assist me in my creations. In this process, any imperfect human stroke of the brush will create a different existence. In comparison, AI can only be chosen.” – Yutong Liu

By the time I have finished writing this, I’ve picked off all my gel extensions.

My keyboard feels faster and slipperier now that my nails aren’t snagging, but I still mis-typed “extensions” three times. Backspace. Backspace. Backspace.

No part of this digital stutter will appear on the screen, but it shapes the sentence anyway, just as plane turbulence skews Yutong’s curved lines in ‘Digital Based Connection’ or a shaking subway carriage misplaces a cursor bird in ‘Across Time’.

This is what ‘Digital Nomads’ so cleverly depicts; even when digital landscapes feel seamless and glossy, they are always led by the body, with a slide of a stylus or an awkward left click. The risk here isn’t that AI will replace artists, but that we give up our context. Yutong’s process resists this both through critique and through her attention to rhythms, gestures, locations, and feeling. AI might mimic or remix style or design, but it cannot feel the clack of the keys or know what it means to mistype a word three times and try again.

About the Digital Dialogues Competition

In April, the ESRC Centre for Digital Futures at Work and Better Images of AI launched a competition to reimagine the visual communication of how work is changing in the digital age. We received over 70 images to the competition from illustrators, artists, researchers, graphic designers, and photographers from all around the world, including Brazil, Hong Kong, Lebanon, France, Uganda, Argentina, Peru, Ireland, the US and the UK. The submissions thoughtfully challenged the dominant stock imagery used to depict digital transformation at work by offering more nuanced, inclusive, and grounded visual representations.

Yutong’s image ‘Digital Nomads: Across Time’ received the Grand Prize, the highest ranking award in the whole competition. Her other image, ‘Digital Nomads: Digital-Based Connection’ was also awarded in the top winning category.

About the author

Harriet Humfress is a London-based undergraduate studying Fine Art at St Edmund Hall, Oxford. Her research explores popular beliefs and myths around AI, and how these ideas of anthropomorphism heighten anxieties around embodiment and labour. Her work covers sound and video installations along with small tactile sculptures that aim to both satirise and inform viewers about how these digital systems cannot be unlinked from human emotion and power structures. Her projects often begin with data collection through surveys and workshops to build an understanding of how people engage with AI in their everyday lives and these data sets then become the material for her works. Alongside her studio practice, Harriet’s writing and research blends both creative and critical approaches, with essays ranging from narrative-driven works such as “A chatbot walks into a therapist’s office” to co-authoring work with We and AI on challenging AI inevitability narratives.

About the artist

Yutong Liu is an award-winning illustrator from China, now based in London as a freelance creative. Her work has appeared in numerous publications and advertising campaigns for clients including The Orion Publishing Group Ltd, Ascend Design, The Alan Turing Institute × University of Edinburgh, Better Images of AI, HiShark Edu, and more. Her illustrations have been recognised by prestigious awards and exhibitions such as the World Illustration Awards (WIA), 3×3 International Illustration Awards, Applied Arts Illustration Awards, ING Discerning Eye Drawing Bursary, Beijing International Book Fair (BIBF), China Illustration Annual Conference (CIAC), the Trinity Buoy Wharf Drawing Prize, and Hiii Illustration Award. Guided by her creative philosophy—“With eyes wide open and heart unveiled—feel life, record its pulse, and embrace its wild beauty”—Yutong’s work captures moments that are both poetic and profoundly human.

Images stacked in cover image: Yutong Liu & Digit / Better Images of AI / CC BY 4.0